|

2047: Virtual Revolution Film review by Thomas M. Sipos |

|

MENU Books Horror Film Festivals and Awards

Pursuits

Blogs Horror Film Festivals and Awards

Other

|

2047: Virtual Revolution (2016, dir: Guy-Roger Duvert; cast: Mike Dopud, Jane Badler, Kaya Blocksage)

Nash (Mike Dopud) is a private investigator working for the corporations in the dystopian year of 2047. He is clearly modeled on Harrison's Ford's Deckard from Blade Runner. Dopud does his best Ford impression. (His best is mediocre.) This was likely encouraged by writer/director Guy-Roger Duvert. The Paris of 2047 resembles the Los Angeles of Blade Runner, right down to the constant rain, neon kiosks, flying cars, trench-coated fighters, ugly brown sky, and high-tech gizmos set against once-great, now crumbling architecture. 2047 also borrows from The Matrix. It's a world in which people like "to connect." A Connector is someone who lives mostly online in virtual worlds. Why live like a loser in a seedy dump when you can be a brave knight slaying dragons, a macho space marine, or a rock star with a harem? There's a virtual world for every fantasy. It's safe. It's cheap. You just connect and you're in. Looks and feels as real as the virtual world in The Matrix. The difference is that you're aware that it's fake, and you can disconnect anytime. Few people do. Nash tells us that 75% of humanity lives mostly online. Even he connects at times. It's to soothe the pain of losing his wife. (Like many noir anti-heroes, he bears an emotional scar.) But at least he disconnects for extended periods. He has a life. True Connectors only disconnect for a quick trip to bathroom, some junk food, then it's back online.

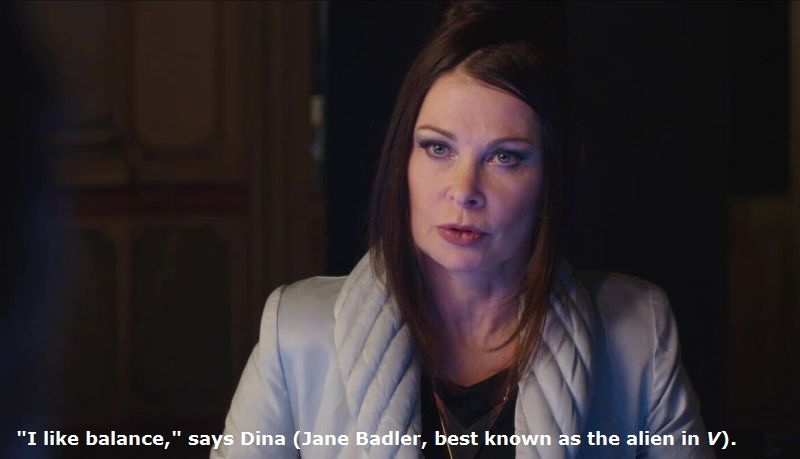

Dina (Jane Badler) tells Nash that things are better this way. Society has "balance." Connectors are easier to control. Cheaper, too. The world government pays them their guaranteed "universal income," and little else, saving money on prisons, policing, education, unemployment benefits (it's not like there are jobs for them), and healthcare. Most couch potatoes die before turning 40. Their universal income pays for the rent, junk food, and access to the virtual worlds provided by the corporations. Corporate taxes fund the world government. The economic system is self-sustaining. "I like balance," Dina tells Nash. Dina is CEO of Synternis, a provider of virtual worlds. The system is good to her. But there's a serpent in the garden. The Necromancers, a terrorist group, are killing Connectors. Should word spread that they're being killed in the real world, Connectors will start disconnecting. Chaos will ensue and society will lose its balance. Through most of the film, Nash hunts Necromancers, much like Deckard hunted Replicants. But unlike the events in Blade Runner, Nash's adventures aren't very interesting. The CGI effects are elaborate, but silly and pointless. Nash hijacks a dead Necromancer's connection, and finds himself in the avatar of a blond warrior woman, fighting a giant transformer robot. There are other battles, with guns and swords, online and off. Despite the big explosions, I was bored.

2047's real power is in its thematic maturity and moral ambiguity. Three groups vie for power. The corporations, the government ("They are allies, but not friends," says CEO Dina of the feds), and the Necromancers. As Nash bounces among them, he grows to realize that he doesn't know who the good guys are. Are the Necromancers terrorists, or freedom fighters? Are they both? Like Morpheus in The Matrix, the Necromancers want to free humanity from a fake virtual world. But unlike the people in The Matrix, Connectors choose to go online. Or is it still a choice once it becomes an addiction? Camylle (Kaya Blocksage), the Necromancer's leader, tells Nash they were wrong to kill Connectors, even for a higher purpose. Her new plan is a computer virus that will shut down all the virtual worlds, forcibly evicting people from their fantasies. Camylle urges Nash to join her fight for freedom. "Can you force people to be free against their will?" Nash asks.

Camylle should have read Arthur C. Clarke's The Lion of Commare, a novella with strikingly similar themes to 2047. Set in the 32nd century, a young man discovers an isolated building full of sleep chambers. Some people have been asleep for months, some decades. The chambers read your mind, providing dreams based on your desires, but keeping you in a state of (happy) suspended animation. You age and eventually die, without ever living. The man wakes people to free them, only to be berated for his unwelcome rescue before they return to sleep. 2047 similarly avoids the sci-fi cliché of the plucky freedom fighter vs. the evil corporation or world government. Before the virus can finish its work, Connectors raise the alarm that their virtual worlds are about to collapse. Panic stricken, they disconnect, form a mob, and storm the Necromancer's base. The mob's savageries against their would-be liberators exceed the cruelties of the Necromancers, the corporations, and the government. Thus do the Connectors form a fourth power bloc. They demand their virtual worlds (their bread and circuses), and they won't be denied. George Orwell observed that revolutions are created by an enlightened middle class leading the lower class against the ruling oligarchy. Whereupon the middle class forms a new oligarchy and re-oppresses the lower class. But the Necromancers' enlightened revolution fails. The Connectors refuse to be freed. The ancien régime remains in balance.

2047 paints a world uncomfortably similar to our own. Corporations and governments feed us, entertain us, lull us into complacency, for profit and stability. Increasingly, people find happiness in online gaming, streaming, and social media echo chambers. It's not implausible that all our favorite online activities will coalesce into single, self-contained virtual worlds. A safe space for everyone, reflecting their preferred values, historical settings, adventures, and companions. You can even change into the sex, race, age, physique, and occupation of your choice, through the avatar of your choice. 2047 has no clear heroes or villains. Everyone has a plausible justification for their cause. Everyone kills to protect or advance their cause. Camylle tells Nash that Synternis killed his wife. That she too was a Necromancer. Dina says it was the Necromancers who killed Nash's wife. That she worked for Synternis. Nash laments, "I'll never know which of you is telling the truth." In the end, Nash escapes his grief by becoming a fulltime Connector. He ponders a final philosophical question. If a virtual world is so real that we can't tell it apart from the real world, then how is it any less real? That same question was posed by a villain in The Matrix. But as Nash is the closest thing to a hero in 2047: Virtual Revolution, his asking it makes this film the anti-Matrix. Review copyright by Thomas M. Sipos

|

"Communist Vampires" and "CommunistVampires.com" trademarks are currently unregistered, but pending registration upon need for protection against improper use. The idea of marketing these terms as a commodity is a protected idea under the Lanham Act. 15 U.S.C. s 1114(1) (1994) (defining a trademark infringement claim when the plaintiff has a registered mark); 15 U.S.C. s 1125(a) (1994) (defining an action for unfair competition in the context of trademark infringement when the plaintiff holds an unregistered mark).