|

Blood and Roses Film review by Thomas M. Sipos |

|

MENU Books Horror Film Festivals and Awards

Pursuits

Blogs Horror Film Festivals and Awards

Other

|

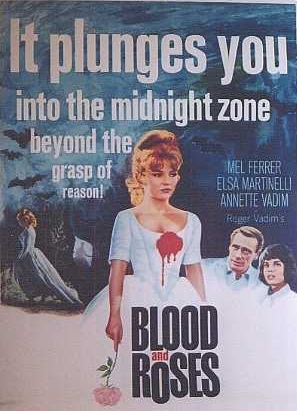

Blood and Roses (French-Italian 1960, dir: Roger Vadim; dp: Claude Renoir; cast: Mel Ferrer, Elsa Martinelli, Annette Vadim; aka Et Mourir de Plaisir)

As mythological creatures go, the vampire comprises so many conflicting aspects (Satanist, monster, victim, parasite, aristocrat, immortal), most films focus on only some of the creature's traits. Blood and Roses focuses on the romantic rather than monstrous. Romantic, in a melodramatic, steamy, Harlequin romance sort of way. Yet in a way that is also sensuous and classy. Blood and Roses is loosely adapted from J.S. Le Fanu's 1871 novella, Carmilla. In Vampire Movies, Robert Marrero describes Blood and Roses as "the only serious (faithful) attempt to adapt le Fanu's Carmilla onto the screen." Well, no. Hammer's The Vampire Lovers (1970) is faithful in ways that Blood and Roses is not, and visa versa. But then, Marrero also misidentifies a still from the film as being from its "classic nightmare sequence." The novella features a young lesbian vampress who seduces her contemporaries. Blood and Roses updates the story, then spans time periods. In the film, the vampress's 18th century spirit (Mircalla) possesses a 20th century woman (Carmilla Von Karnstein, played by Annette Vadim), then through her body pursues the man they both love (her Von Karnstein cousin, played by Mel Ferrer). Together, Mircalla/Carmilla seduce, drain of blood, and kill Ferrer's finacée (Georgia, played by Elsa Martinelli), hence a tepid lesbian scene. Tepid by today's standards, although the scene was excised for the film's initial US release. Nor is there much blood in Blood and Roses. Deaths, when they occur, occur offscreen. Even so, Carmilla's (offscreen) murder of a servant girl is emotionally horrific, because we feel sympathy for both vampire and victim; all-too-rare in horror films, where the vampire is usually either monster or sympathetic hero. Blood is used artistically rather than gorily. Bright red blood soaks through a bright white dress, but as it's only a dream, the horror is mitigated. Bright red blood also provides the sole color in a surreal black & white dream sequence. (You know you're watching an art film when some of it's in color, some in black & white). Blood and Roses is gracefully shot. Early on, as Carmilla relates her ancestor's (Mircalla) history to assembled guests, a fluid POV shot ambiguously suggests the presence of her spirit. Carmilla speculates about her ancestral vampire's thoughts and feelings as the POV glides through the room, her guests staring back into it. (Reminiscent of Last Year at Marienbad.) The "entity" behind the POV may be the vampire's spirit, or it may be the imaginings of the storyteller and her guests. There is much self-conscious artiness. Pining over her unrequited love for her cousin, Carmilla wanders past fluted columns on his Italian estate, Mircalla's regal 18th century white dress billowing about Carmilla. Resplendent fireworks intercut Carmilla's beautifully brooding wanderings, punctuating her suppressed passions. Her dark heartsickness contrasts with the colorfully costumed guests reveling at a masque ball -- honoring Georgia's engagement to Von Karnstein. Carmilla must feign joy over the very cause of her heartbreak. Beautiful, brooding, heartbroken -- the Goth's ideal of the romantic vampire! Carmilla's suicidal depression over Von Karnstein's impending marriage leaves her easy prey for Mircalla's spirit, whose voiceovers guide Carmilla to her tomb, where she possesses Carmilla's body. Some may regard the voiceover device, especially atop the fireworks and perfume commercial mise-en-scene, to be overmuch. Some do regard Mircalla's melodramatic monologues to be bathetic.

The Overlook Encyclopedia says: "Clearly intended as an art-house horror movie, it aims for a dreamily languorous rhythm which never quite manages to overcome the obstacles posed by stilted performances (Ferrer in particular), bathetic dialogue, and direction too prosaic to achieve the necessary intensity." While I can see where Phil Hardy is coming from, Blood and Roses works for me. Yes, I suppose some of the dialogue evokes the adolescent poetics of a Meat Loaf CD. Von Karnstein's mask does indeed resemble a Bat Out of Hell. Yet I find the film to be poignant rather than bathetic, and saw no problem with anyone's performance, Ferrer's included. But then, I like Meat Loaf's music. If Meat Loaf's aesthetic sensibility resonates with you, chances are you'll like Blood and Roses. That may sound an odd comparison, yet while the film lacks Meat Loaf's aggressive, leather-clad biker machismo, it shares an impassioned, operatic undercurrent. Carmilla is forever wandering about the estate in Mircalla's 18th century white dress, proud and dignified (and resembling the siren in Meat Loaf's I'll Do Anything for Love video, albeit more subdued). Behind Carmilla are backdrops of crumbling castles and autumnal colors. And yet, aside from their perfume commercial beauty, Vadim/Renoir's panoramic long shots function aesthetically. By evoking an impressionistic painting, the composition subsumes Carmilla into the old world of her aristocratic ancestor. Long shots usually disempower a character, the small character overwhelmed by her surroundings. Yet in Blood and Roses they achieve an opposite effect. Although Carmilla is arguably disempowered (because she is possessed), her regal bearing as Mircalla (in Carmilla's body) is empowered by the compositions. She walks past castles and columns and neatly aligned trees with confidence and dignity, seemingly in command of her aristocratic surroundings. In the hospital dream sequence, the black & white photography, like the impressionistic composition, draws Carmilla back in time toward the vampress possessing her. In The Vampire Film, Silver & Ursini say of the black & white photography (and masque ball): "These events propel the film backwards figuratively into a dark age." That is, to Millarca's age.

Of course, black & white also heightens the dream's surrealism, and heightens its horrors. Bright red blood appears that much starker. Robbed of the warmth of colors, the nurses' mannequin-like movements appear coldly robotic, unnatural, as impersonal and antiseptic as death. If I seem to spend overmuch time discussing the colors and composition and mise-en-scene, well, this is an art film. Blood and Roses is intended as a visual feast, rather than a suspenseful story. (An aural feast too -- its classical soundtrack is passionate and romantic). A film meant to be accepted and savored for its sights and sounds and passions, rather than analyzed. In Dark Romance, David J. Hogan writes: "Vadim sacrificed logic and narrative at the altar of imagery.... Blood and Roses is a predominantly visual exodus through some very subtle psychological territory." Blood and Roses won't convince you of its story if you have trouble suspending disbelief. You'll either accept the film on its own terms, or you won't. Blood and Roses seems little-known among horror film buffs, yet avid fans of "vampire romances" will likely regard it as one of their favorites -- should they ever stumble across it. I'm no fan of "vampire romances," not especially, yet Blood and Roses has long been one of my favorite horror films (say in the Top 100). Yes, Hardy is right. Blood and Roses was "clearly intended as an art-house horror movie." And as such, it's one of the best. Review copyright by Thomas M. Sipos

|

"Communist Vampires" and "CommunistVampires.com" trademarks are currently unregistered, but pending registration upon need for protection against improper use. The idea of marketing these terms as a commodity is a protected idea under the Lanham Act. 15 U.S.C. s 1114(1) (1994) (defining a trademark infringement claim when the plaintiff has a registered mark); 15 U.S.C. s 1125(a) (1994) (defining an action for unfair competition in the context of trademark infringement when the plaintiff holds an unregistered mark).