|

Stage Fright Film review by Thomas M. Sipos |

|

MENU Books Horror Film Festivals and Awards

Pursuits

Blogs Horror Film Festivals and Awards

Other

|

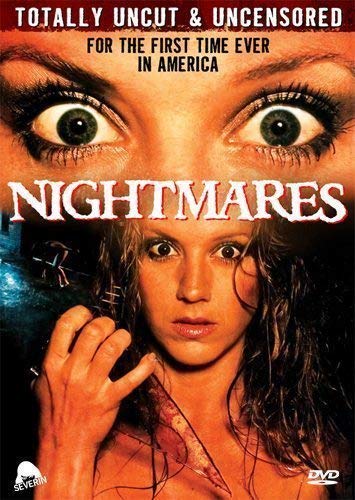

Stage Fright (1983, dir: John Lamond, cast: Jenny Neumann, Gary Sweet, Nina Landis; aka: Nightmares)

A little girl (Cathy) is traumatized upon seeing her mother fornicating with an illicit lover. Later, Cathy's unsuspecting daddy bids goodbye as Cathy and mommy drive off on a road trip. Cathy awakens in the back seat of the car to espy the lover fondling mommy's thighs while she's driving. Cathy panics and intervenes. Mommy is thrown through the windshield in the resulting accident. When Cathy tries to drag mommy back into the car, she inadvertently slits mommy's throat against windshield shards. Recovering in a hospital, Cathy overhears a nurse mention that Cathy killed her mom. Daddy accuses Cathy likewise, apparently ignorant or indifferent that his daughter was defending him from cuckoldom. With all that guilt and ingratitude, what's a girl to do? Cathy attacks a hospital employee with a glass shard. Do you begin to detect a familiar pattern? Flash forward. Cathy grows into adulthood, changes her name to Helen (played by Jenny Neumann from Hell Night), and becomes an actress who is cast in a theatrical "comedy about death." Actors hide in their roles and Helen is always in character. The character she portrays onstage, and the character of normalcy offstage. In her offstage role, Helen evokes Norman Bates. She strives to remain self-possessed but lives on an emotional edge, her composure masking inner turmoil. Like Norman, she fears her sexuality. Helen tells Terry, a fellow actor, that she's "Never had a boyfriend. Never been allowed." Suppressing her trauma, Helen allows Terry to kiss her. It's not something she allows lightly. So when she catches Terry peck the production manager at lunch, Helen bolts from the cafeteria, distraught. Terry follows Helen to her apartment, outside which Terry hears Helen arguing. "I trusted him!" Helen screams. "Then you're a fool!" a deeper voice responds. When Helen leaves, Terry knocks on the door. If you've seen Psycho, you won't be surprised to learn that no one answers. Helen also dreams. Dreams about death. (Stage Fright is aka Nightmares -- not to be confused with the horror anthology film of the same name.) Which is curious, because a string of murders is plaguing the theater. When Helen relates her nightmares to Terry in an park, he responds, "You're strange." No kidding. Stage Fright is a real treat for fans of poverty row horror. Aside from an interesting story performed by a respectable cast, the film exhibits creative attempts to stretch the budget. For instance, the above park scene is tightly framed, indicating the filming was done sans permit, passersby just beyond frame. But while the tight framing was likely pragmatic, it both enhances our intimacy with Stage Fright's characters and fosters a claustrophobic atmosphere.

This tight pragmatic framing reappears whenever needed to hide something off camera. The frame widens whenever there is nothing to hide, as when filming the actors performing on stage, but tightens when the director (George) approaches the stage to thunderous applause. That, and the low camera angle framing George's head with the ceiling "behind" him, both emphasizes his vanity and effectively hides what is doubtless and empty theater. (Extras cost money.) Thus this shot simultaneously serves the pragmatic need to conceal the empty theater, and the aesthetic goal of illustrating George's character. Another example of Stage Fright's pragmatic aesthetics is how it avoids aiming the camera at a nonexistent theatrical audience by instead shooting the play's rising and falling curtain from myriad stylized angles. These sharply skewed camera angles not only hide the empty theater, but they also effectively underscore the emotionally unstable life of actors and the insecurity created by the threat of further killings. (By pragmatic aesthetics, I mean when a filmmaker puts budgetary production compromises to aesthetic effect. Forced to compromise on location, lighting, whatever, the filmmaker uses that limitation in a way that enhances the theme or story. I first used the term in my essay, "The Pragmatic Aesthetics of Low-Budget Horror Cinema," published under another title in Midnight Marquee #60. For a fuller explanation, see my book, Horror Film Aesthetics.) Harsh lighting evokes documentaries, and thus it creates a concrete immediacy that heightens intimacy with a film's characters. Stage Fright's characters benefit from such harsh lighting, even if they were only lit that way because the filmmaker had little time for complicated lighting setups. Stock footage of theater crowds pad the film, along with canned crowd murmur. Offhand remarks mixed into the murmuring are not attributable to any specific theatergoer. The editing it rough, the film stock of various ASAs, but it all works. (Hey, when Oliver Stone mixed film stocks for Natural Born Killers, it was called genius). Despite (or perhaps because of) low-budget restraints, Stage Fright conveys a poetical lyricism. Scenes are quick, often just a line or two, fading in and out in rapid haiku succession. Helen begins a scene by saying to Terry: "I can't love you. Much as I want to, I can't." "I can love you," he responds. "You fool. Cathy won't let you." Fade out. This minimalist approach, fading in and out of brief scenes, was used to great poetic effect in Stranger Than Paradise (1984). Jim Jarmusch developed it due to budget constraints, filming Stranger Than Paradise piecemeal, as money was raised. Again, Jarmusch was called genius. Why not Stage Fright director John Lamond? Stage Fright's stereotypical characters drawn from the world of Theater jell well with what remains in many ways a traditional slasher film. Their superstitions and neuroses form the subtext for the slasher's psychosis. An actress traumatizes her peers by whistling backstage. After one murder, she is reminded, "You're to blame! You whistled! This production's jinxed!" George is shocked upon seeing an actor in green. "Never wear green!" When not insulting his actors, George spouts artsy-fartsy gobbledygook. "The meaning of the lines doesn't matter. It's the juxtaposition and rhythm of the words." A foppish critic (Bennett) delights in writing negative reviews and propositioning both actors and actresses alike. Stage Fright utilizes standard slasher film aesthetics. POV shots conceal the killer's identity. Jarring melodramatic music heralds ominous events. Characters turn stupid at the most inopportune times. The drunken Bennett, staggering through the theater's basement just as the killer bursts through a glass door, simply remarks, "Jesus, why'd you do that for? You scared the fucking daylights out of me." But instead of fretting over this unusual entrance, Bennett ignores his own query and adds, "Well don't just stand there. Help me find my lighter." Whereupon the killer picks up a glass shard...

Stage Fright is a splendid slasher film, but not so clever as to defy expectations. If you can't guess the killer's identity early on, you haven't been watching the subgenre. Even so, Stage Fright does end on a surprise twist, similar to that in Intruder (1989). Stage Fright is also marred by crass sadism (victims require prolonged and repeated stabbings to die) and gratuitous nudity, but is an overall enjoyable excursion into the world of Theater, delineating all its backbiting jealousies, backstage gossip, and petty power politics within a slasher film context. Jenny Neumann makes for a plucky Helen. True, Stage Fright features very rough productions values. It's the sort of unpolished slasher effort that many critics deride as scrapings from under the bottom of the barrel. And yet, the film's very roughness lends it an authentic sensibility. Aficionados of ultra-low-budget horror Z-films (e.g. Don't Look in the Basement) will find much merit in Stage Fright. Review copyright by Thomas M. Sipos

|

"Communist Vampires" and "CommunistVampires.com" trademarks are currently unregistered, but pending registration upon need for protection against improper use. The idea of marketing these terms as a commodity is a protected idea under the Lanham Act. 15 U.S.C. s 1114(1) (1994) (defining a trademark infringement claim when the plaintiff has a registered mark); 15 U.S.C. s 1125(a) (1994) (defining an action for unfair competition in the context of trademark infringement when the plaintiff holds an unregistered mark).